This June was not the best time to graduate from college. Employers hired 43,000 fewer recent graduates than they had in 2008. Michael Jackson died. And as if the world weren’t already coming to pieces, the World Health Organization declared that swine flu was a global pandemic.

Given the circumstances, I leapt at a summer job opportunity in China, a country about which I know very little. I somehow escaped high school without a course on world history: the closest GHS came was freshman year’s ‘World Themes,’ which defined the ‘world’ as the US and Europe. I hardly improved on the record in college, where I focused on comparative government but, yet again, left out China.

Contrary to appearances, I have not been living under a brick, and I was eager to learn more about the country that houses one out of every five living people on this planet. I backpacked around China for ten days last summer with a Chinese-American friend, but the Olympics were in full swing and the entire country was on its best behavior. Factories were shut down to improve air quality, private cars were taken off the road, and guides in white and blue outfits hovered at every corner, eager to direct hapless foreigners to their destinations. I enjoyed myself, but I wanted to see what China was like outside of the big tourist-friendly cities. The job opportunity, teaching English in the heart of Guangdong province, seemed like it would do the trick. Guangdong is the powerhouse of China’s industrial south, adjacent to Hong Kong. Guidebooks describe it as ‘charmless,’ ‘uninteresting,’ and, my favorite, ‘a wasteland.’ I packed my bags.

Just before I flew over, a dispute at a factory in Guangdong sparked riots in Xinjiang, a province in northwestern China that is predominantly Muslim. Around 180 people were killed and 700 injured in some of the worst ethnic violence China has seen in recent years. I’d had a hunch China in the summer of 2009 was going to be very different from my experience in 2008. Now I was certain it would be.

The border crossing from Hong Kong confirmed my suspicions. The cheerful blue-and-white-clad welcomers were replaced with rifle-toting officials who surrounded my bus and pointed what looked like pistols at the forehead of every passenger. They were checking our temperatures – the ‘pistols’ were thermometers – in an effort to make sure that no one with a fever entered the country. Swine flu hysteria was just beginning to hit China.

I never bought in to all the fuss surrounding swine flu: yes, it’s new, and yes, it is highly contagious, but in the end it is a relatively minor illness that tends to pass after a few days and only seriously endangers people already in fragile health. Administrators at my college didn’t share my nonchalance: they banned handshakes and hugs throughout graduation week. But students, professors, and families alike laughed at the heavy-handedness of the policy and universally ignored the ban.

The reaction has not been so light-hearted in China. In a country of 1.3 billion people where 43% of the population lives in extremely crowded cities, it hardly seems worth the effort to try and contain a virus so contagious and relatively innocuous. However, memories of the 2002 SARS epidemic are fresh in China, and many feel that the government did too little too late to adequately address that health scare. The Communist party is taking no risks this time around. Strict quarantine has been imposed on people exhibiting flu-like symptoms. The detention of foreigners, mostly from the US and Great Britain, has kept consulates busy, though in this case at least the Chinese government has the upper hand: it was the American Center for Disease Control which generated so much of the hype around swine flu in the first place.

On July 27th, another counter-flu initiative was sent from the hallowed halls of the Communist Party: all schools, summer camps, and conferences were to be terminated immediately. The logic, if it can be called that, behind the initiative was that children’s parents could take care of them better than summer camp administrators. The reality was that millions of sick people flooded into the national transportation system. But at least they were on their way to becoming their family’s problem instead of the state’s.

|

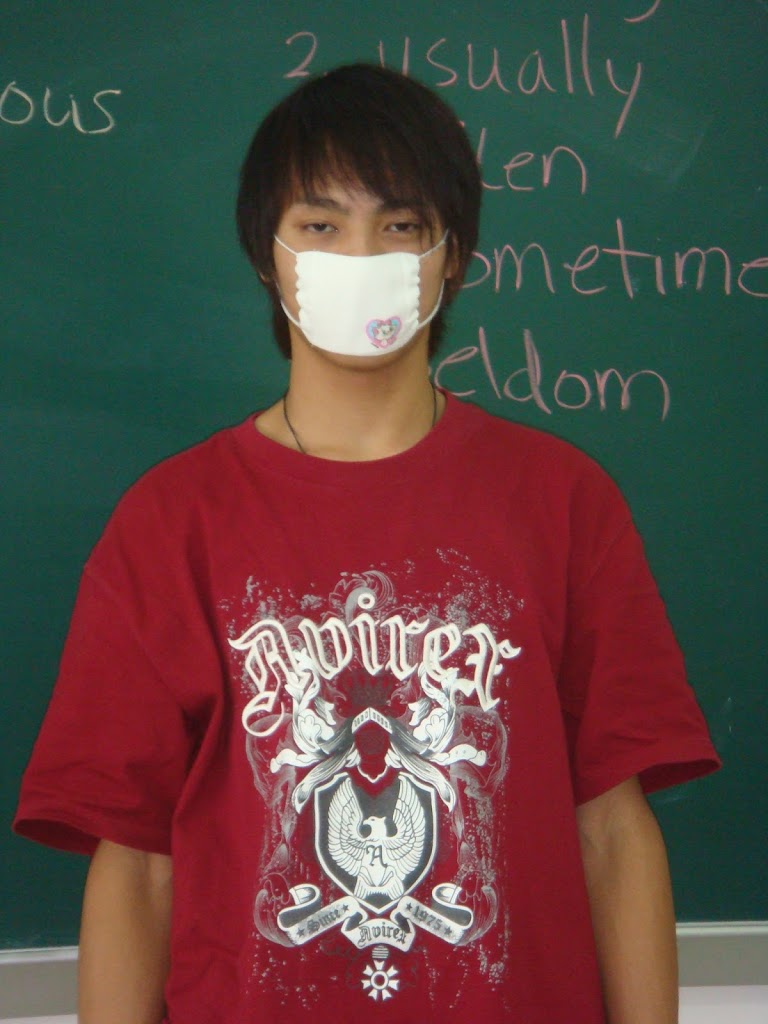

| Jacky Chen, my oldest student. |

The ban shut down my school, of course, so I’m now out of a job in an unfamiliar, flu-crazy country. Let the fun begin.