Cairo is so hot right now. Three of my coworkers have taken vacation there in the last month, as has Jennie, one of my fellow-sufferers in Hakan‘s Turkish classes (yes, I fulfilled my New Year’s resolution to resume Turkish classes with my favorite quintolingual chainsmoker). And of course Kate was there in the fall, stealing the hearts of merchants and taking sublime pictures (scroll down for Cairo, Luxor, and Aswan), as she is wont to do.

The review from these highly respected sources runs something like Samuel Johnson’s assessment of Paradise Lost: ‘it is one of those books the reader admires and lays down, and forgets to take up again. No one ever wished it longer than it is.’

Cairo is one of the great cities of history, and the pyramids, like PL, deserve a chance to cast their spell on you. But no one I know seems to want to go back to Cairo. It is disorganised, overrun, filthy. In Kate’s words:

‘I felt cramped, claustrophobic, uncomfortable [in the Egyptian Museum]. In fact, this is how most of Cairo made me feel. It drew many similarities to feelings and experiences I had in Damascus. The same dirty grittiness of that comes from thousands of years of inhabitance. The same overwhelming numbers crowding streets and buses. You could feel the oppressiveness of the poverty. You could see the differentiation between wealth and the lack of it. You could taste the pollution; the smog hangs over the city like a hot summer haze.’

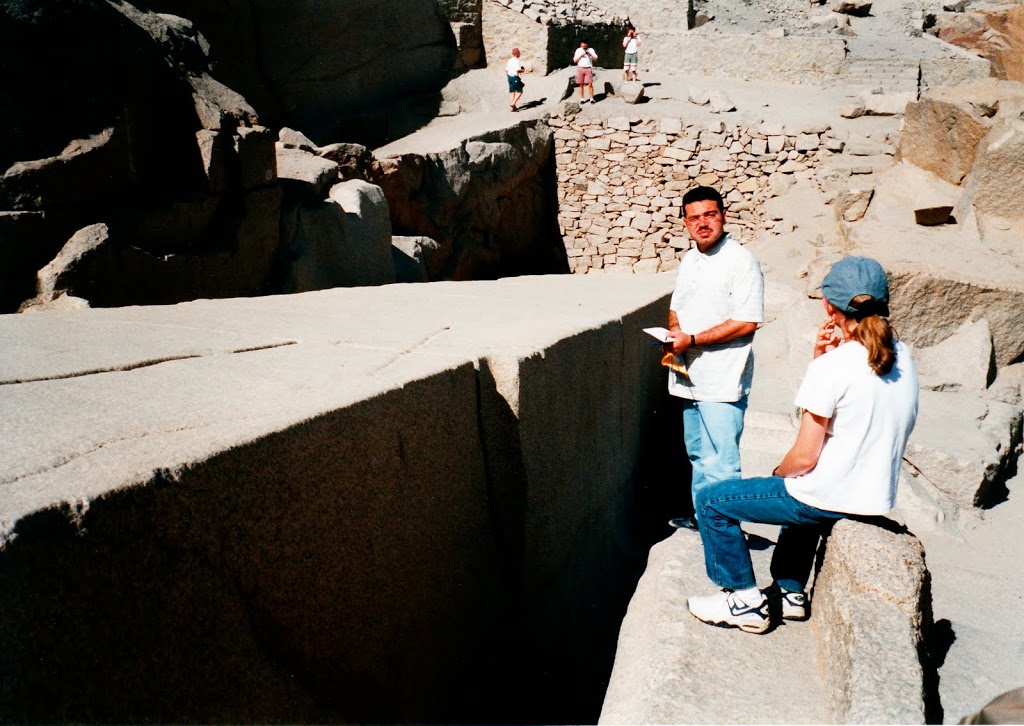

I visited Cairo in 1998, when I was gripped by an Egyptomania so severe I taught myself how to read hieroglyphs. My family fondly remembers how I would correct our clueless guide, Hani, when he botched the stories behind my favorite temples and archaeological sites.

For my part, I have blocked this aspect of my childhood – obnoxious smartassery – from my memory. What I do remember, though, is disappearing into the upper reaches of the bazaar with my brother Edward one day and being offered a fistful of marijuana for about $5. Even in my childhood innocence I could tell that was a good deal (we didn’t take it).

Cairo’s bazaar was the thing that bothered my friends the most. The constant heckling, fear of bag snatchers, and wildly inflated prices do not make for a relaxing vacation. Jennie, who returned last week, had plenty of horror stories about the street scene, and shared some during one of Hakan’s smoke breaks.

‘Cairo,’ she concluded, ‘makes Istanbul feel as clean and orderly as Copenhagen.’

Petri, a forty-something Dutch businessman who recently joined our class, shook his head. ‘If you could have seen Istanbul when I first came here in 1988! It made Cairo look – well, not clean and orderly, but – I suppose cosmopolitan. You couldn’t walk a foot in Istanbul with your wallet hanging out of your pocket. You couldn’t see the other side of the street for all the smoke. And the hecklers would loop their fingers through your belt loops until you bought something from them.’

I was surprised to hear this. I know Istanbul has gone through significant changes over the last 20-30 years: take, for example, the fact that the population has gone from 2 million to 20 million. But to my mind the Istanbul of 1988 was a relative backwater, a faded ghost town when compared to its past and future vitality. What, I wondered aloud, changed between then and now to make Istanbul the relatively clean, European city it is today? Was there some mayor who cleaned up the streets, Giuliani-style, locking up the crazies and making the peddlers buy permits?

‘It’s much simpler than that,’ said Hakan. ‘People got richer.’

Could it be that straightforward? True, Istanbul’s population boom corresponded with a massive increase in Turkey’s wealth: inflation-adjusted GDP grew from $90 billion to $270 billion in the ten years between 1988 and 1998, and to $734 billion by 2008, according to the World Bank. The structure of the economy changed as well, with more than 15% of the workforce shifting from blue-collar jobs in agriculture and manufacturing to white-collar service jobs.

Yet the World Bank statistics never take into account the black market, which in Turkey is generally estimated to account for 20-25% of all economic activity. Nor does it seem likely that all of Istanbul’s 18 million new residents have managed to find jobs more lucrative than begging, petty theft, and selling fake sunglasses. But take a walk down any street outside of Sultanahmet, Istanbul’s touristy center, and you’ll realize something must have worked. You’re more likely to be heckled in Harvard Square than on Istiklal Cd, Istanbul’s main shopping and nightlife artery.

Reason No. 25601 I’m glad I moved to Istanbul: it doesn’t fit the models I’m used to, and so is constantly intriguing. Reason No. 25602: I have too many pairs of fake Ray-Bans already.

Share this: