When, last spring, I first thought of moving to Istanbul, I talked over the idea with Kate, who I’ve mentioned quite a few times in this blog. The logic went something like this: instead of moving back in with my parents while I figured out what I wanted to do with my life, I would move somewhere where the rent is cheap and maybe get to know a new part of the world. It sounded logical, she said. It even sounded like fun. We flirted with the idea of moving over together, but as our summers took us in different directions – her to work in Boston, me to China and the former Soviet Union – it looked more and more like she would be starting work in New York City and I would be arriving in Istanbul on my own.

Which is what happened, sort of. I arrived in Istanbul and started to look for work, and Kate enrolled in a job training course. Or at least I thought she had until she wrote me and told me she’d found a good fare and bought a ticket to Istanbul.

|

| Inside one of hundreds of cave churches |

I didn’t manage to keep her in the city for long. Armed with a sturdy backpack and a sense of adventure that makes me look like a hermit, she set off for Syria, Palestine, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Egypt, Iran, Pakistan, India, and Nepal, or so was the plan last time I checked. But first she eased her way into life on the road by exploring Turkey.

It didn’t take more than a single entry on her blog to convince me to put my own pack back on. The fact that the correspondent I had been working with had decamped to Pakistan for an indeterminate period, and that flights to Capadoccia, where Kate was, were $30, sealed the deal. I left the next day.

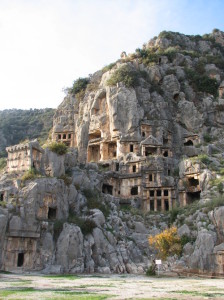

Capadoccia, in central Turkey, has some of the most interesting geology on earth. Four volcanoes covered the region in lava a few millennia ago. Persistent winds wore the soft stone into cone-shaped towers, and rivers carved colorful gorges through layers of pink, white, and yellow lava.

From the 5th century onwards, Capadoccia became a refuge for early Christian sects deemed heretical by the orthodox church. They burrowed into the stone cones and, sometimes, underneath, digging subterranean cities with as many as eight stories. They eeked a living out of miniscule farms fertilized with pigeon droppings. To this day, it is said that a man won’t be taken seriously as a suitor unless he has a sizable flock of pigeons.

|

The most elaborate cave churches are covered in frescoes,

most of which date to the 11th century. |

Many Capadoccia natives have capitalized on the exotic appeal of their homes by turning them into inns. I discovered Kate lounging on a bed of carpets on the deck of the excellent Kelebek Cave Hotel soon after I arrived. Though we were staying at the also excellent Kose Pension – on the roof, no less – she had, characteristically, already made friends in town. Ali, the innkeeper, was pouring wine liberally, and it was established that there was nothing that could possibly be done with the afternoon but watch the colors of the valley change as the sun set.

My second day, we turned to the serious business of exploring. Life in the underground cities could not have been much fun. The tunnels are tiny, designed so that attackers would be forced to move slowly and therefore killed easily. It may be a claustrophobe’s nightmare, but the little girl in me thought it was one of the coolest things I’d ever seen. Cowboys and Indians seem so quaint compared to cave-dwelling heretics and pagan/Muslim/Orthodox crusaders.

|

| The Goreme ‘Open Air Museum’ – a series of remarkable churches in the most widely-visited town in the region. |

We didn’t have to guess at what life would be like in the cone towers because Ali invited us to his friend Apo’s place for a barbecue. As the lamb was grilling, Apo showed us his sumptuous (well, for a cave) living room. It was covered in Turkish carpets and tapestries, which I had expected, and had a wireless router, which I had not. Ah, modernity.

Most of Apo’s friends didn’t speak English, but I bonded with one who was playing a saz, a six-stringed lute-like instrument that is common in Turkey. He showed me some basic chords and we began to sing together, no doubt to the horror of anyone who was listening.

I had trouble falling asleep on my overnight bus home. From the center to Istanbul in the northwest is a solid eleven hour drive through the Anatolian heartland. Occasionally the bus would shudder to a halt next to a roadside stand that had appeared, unannounced, out of the surrounding blackness. A small crowd, usually old women, was waiting at each, clutching small cloth satchels and huddled against the late October chill. They shuffled on board, taking the places of a handful of equally wizened old women who melted into the night outside, and then promptly fell asleep.

I did manage to drift off a little past two, but woke with a start just past three. A woman the color of dusty hills and at least as old had fallen asleep with her head on my chest. She was wearing the drop-seam pants that have recently become fashionable (‘genie pants’) but are in fact native to this region. The story behind their origin goes something like this: one early Christian sect believed the Messiah could be born again at any time, so they had their women wear drop-seam pants that would catch baby Jesus II when he popped out. The pants would also help hide the baby in case Herod II decided to come try to kill him. Evidently, no one is going to notice you walking around with a baby tucked in your pants.

When I woke up again in Istanbul, the old woman had disappeared back into the countryside, far from the skyscrapers and housing complexes of the city I now call home. Reflexively, I checked for my wallet, but I really didn’t need to. As a Turkish friend explained to me, Turks protect guests in their country – they use the word guest, not tourist – with almost religious passion. This is changing in the increasingly developed tourist hubs of Old Istanbul, Izmir, and Troy, but I still feel safer in Turkey than in, say, Paris or New York City. Kate, meanwhile, continues to defy anyone’s notion of what is safe for a small blonde woman by hitchhiking around the Middle East. If I could think of a single place in the ‘west’ where she’d be as safe doing that I’d feel slightly more charitable towards the people who have managed to convince conservative America – make that most of America – that the Muslim world is full of bloodthirsty fanatics.

Getting there: Fly into either Kayseri or Nevsehir on one of several cheap flights a day from Istanbul’s airports, then take a 20 lira one hour shuttle to Goreme. By bus or car, it’s an 10 to 11-hour ride from Istanbul or Izmir. You could stay in the slightly more upmarket Uchisar, but we recommend Goreme for its range of accommodation options and proximity to the best sites.