Foreign Policy, the rag founded by Samuel P. Huntington, has become a lot more fun (and less dignified) recently. First there was the whole zombie thing. It started with the innocent use of the word zombie (ie, reanimated corpse) to describe the proposed three-state solution to the Israel-Palestine crisis that was being bandied around back in January 09. Then, in August, there was the first of many blog posts by Daniel Drezner:

how international relations theorists would cope with zombie attacks, soon followed up with March’s

Dawn of the Theories of International Politics and Zombies and June’s

Night of the Living Wonks.

Another favorite topic, after the undead, is failed states. They make for interesting photo essays – from Postcards from Hell to The Worst of the Worst (subtitle: bad dude dictators and general coconut heads) to Planet War. The one that stuck with me most, however, is Lifestyles of the Rich and Tyrannical: a short exploration of the lavish real estate holdings of some of the aforementioned bad dude dictators.

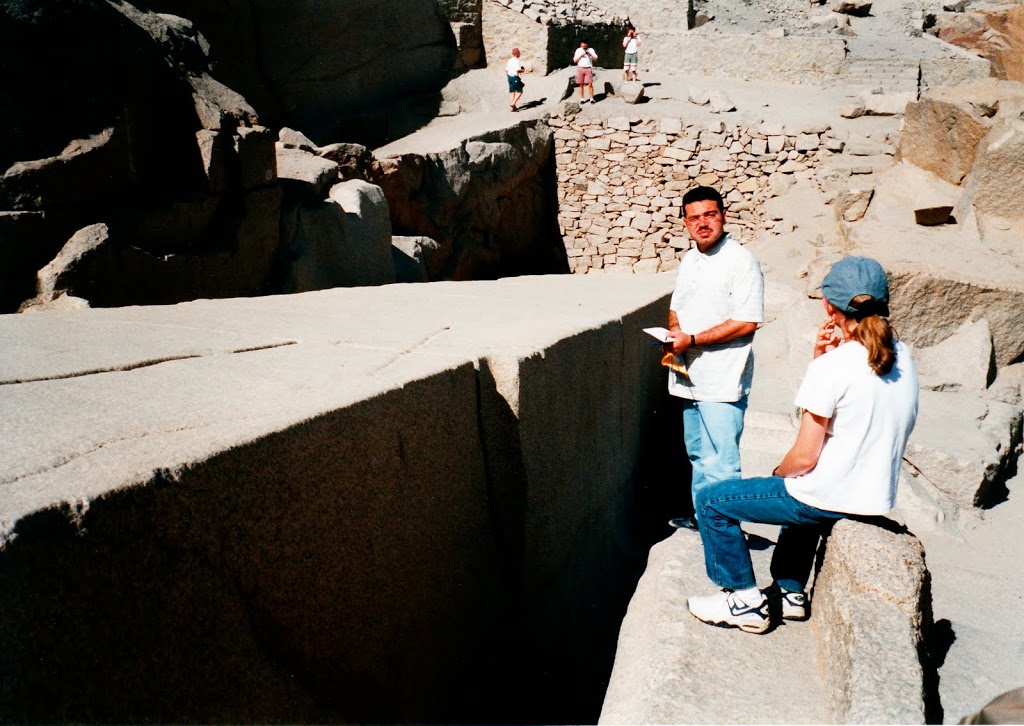

Perhaps it just seems topical. I recently returned from Oman, home to the enigmatic Sultan Qaboos and his (estimated) twenty-four palaces. True, he’s had forty years to feather his nest, having deposed his father in 1970. And judging by the looks of his central palace in Muscat (left), I don’t blame him for trying again (and again, and again).

Perhaps it just seems topical. I recently returned from Oman, home to the enigmatic Sultan Qaboos and his (estimated) twenty-four palaces. True, he’s had forty years to feather his nest, having deposed his father in 1970. And judging by the looks of his central palace in Muscat (left), I don’t blame him for trying again (and again, and again).

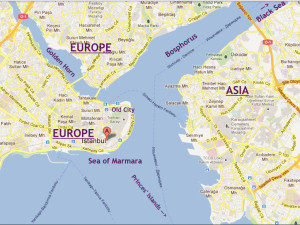

Oman is the second-largest country on the Arabian peninsula, and by most accounts its most beautiful. It’s remarkably peaceful, especially given it shares a land border with Yemen, is 21 miles from Iran, and hosts a large port in close proximity to Somalia.

I was there for two weeks on a business trip – long enough to learn three phrases in Arabic and meet two members of the royal family (one of which took the opportunity to extol, at length, the virtues of Russian hookers as opposed to Chinese ones).

Writing about economic development in the Gulf states, as I have since December, has been an eye-opening experience. With some notable exceptions, these countries were largely sand dunes populated by nomadic tribes until the middle part of the last century. What the Arabs have been able to produce in the last sixty years – albeit with a lot of help from guest workers – is nothing short of revolutionary. When His Excellency Sultan Qaboos came into power in 1970, less than a third of the country was literate, and its people either lived in a medieval-style fort or a tent (the remains of the former dot the capital’s craggy shoreline).

‘If you wanted to go outside at night, you had to carry a sword,’ my driver, Hashim, told me. He was born sometime in the fifties, though he’s not sure exactly when.

Today, 95% of the Omani population is literate and almost everyone speaks fluent English in addition to Arabic. The roads of the capital, Muscat, are wide and nearly traffic-free, there’s air conditioning everywhere, and the tap water is potable (which is more than you can say of Turkey). Life expectancy is in the 70s and the per capita income is $24k a year. Which, incidentally, is an order of magnitude greater than most of my American college-educated friends made last year.

There are two obvious reasons this kind of supercharged modernization was possible. First, the GCC’s rulers – absolute monarchs, or emirs, or sultans – have little need to pander to that pesky bourgeois notion of democracy, thanks to decades of oil-funded public largesse.

In true Maslowian fashion, the idea of democracy doesn’t hold much appeal to the generation who are experiencing life in a safe, stable country for the first time. I asked Hashim if he would like to vote:

‘Why would I do that?’ he said. ‘I live a good life.’

The only country in the region to make any concrete steps towards democratic rule is Kuwait, which formed its first elected National Assembly in 1963. The experiment has not been a smooth one. Critics blame the National Assembly for hamstringing Kuwait’s development through petty, corrupt, and/or incompetent governance. The decision in January to take over responsibility for all consumer loans – effectively, a bailout for some of the world’s least credit-worthy spenders – is only one example of how the short-term interests of politicians worried about reelection are trumping the long-term viability of the country.

I remember writing an essay about how democracy is self-evidently the best form of government back in sophomore year of college. It has since been lost to the sands of time (read: computer failure). I still believe it is, in theory. But subsequent courses back in the Ivory Tower – and, of course, being hit over the head with the disparity between the developing country I live in, a ‘democracy’, and places like Oman – have made me think a lot more about when and where democracy can be reasonably introduced.

Tocqueville thought democracy would lead us a future of equality and blandness. Robert D. Kaplan, in his excellent, if controversial piece on why democracy is bad for developing countries, has a slightly different vision. Kaplan believes our love of the bottom line will lead us to a globalized, and therefore anarchic, economy, which will necessitate tyrannical rule to restore stability. The tyrant will be The Corporation, or the Military-Industrial complex, as the problems of the world are too vast to be controlled by one bad dude dictator and/or coconut head.

In Oman, at least, the promise of democracy – the premise of democracy – is seen by many as dubious. The financial crisis has if anything strengthened the average Omani’s (and Oman-based expat’s) conviction that Sultan Qaboos’s measured approach to development is best for the country (the country continued to grow and saw a minimum or projects go on hold while neighbors like Dubai tanked). One man I talked to, the Dutch GM of a major oil company’s Oman operations, went so far as to call Qaboos ‘a philosopher king in the Platonic fashion.’

In Oman, at least, the promise of democracy – the premise of democracy – is seen by many as dubious. The financial crisis has if anything strengthened the average Omani’s (and Oman-based expat’s) conviction that Sultan Qaboos’s measured approach to development is best for the country (the country continued to grow and saw a minimum or projects go on hold while neighbors like Dubai tanked). One man I talked to, the Dutch GM of a major oil company’s Oman operations, went so far as to call Qaboos ‘a philosopher king in the Platonic fashion.’

As an American raised by a Palin-loving ex-Marine (ex-Marine in the Palinic fashion?) on the good old fashioned values of hard work, industry, and disdain of the Washington establishment, I’m uncomfortable with Omani king-worship. And, for that matter, the docility of most of the people in the Gulf in the face of the abuses of their governments. Yet I also realize I grew up in a state that provided me free education, a childhood untouched by violent or arbitrary crime, and an environment where blog posts comparing politicians to soul-sucking zombies are laughed at and not censored.

I’m sure there are plenty of people doing fascinating work on human development. Some day when I don’t have 26,000 words of copy to write in a month I might have more time to get into it.

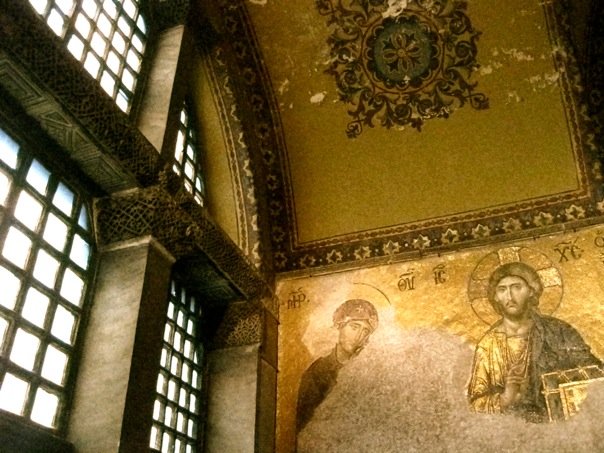

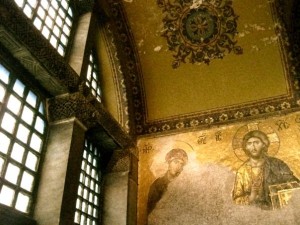

That, and the pollution in Istanbul is getting to me. Artistic wealth, generous inhabitants, and baklava this city has in spades, but emissions controls not so much. My brother Robert is visiting and we spent much of Saturday walking through unexplored neighborhoods and hiking along the top of the 4th century Theodosian walls (the picture to the right is me talking to a dog in the slum next to the northern end of the city walls). Being able to wander aimlessly through centuries of history in a tank top in the middle of winter is a luxury I wouldn’t have even dreamed of in my four years of purgatory in freezing Cambridge. But, greedy as always, I would love to be able to spend the day outside and not feel like I smoked a pack of car-exhaust-flavored cigarettes at the end of it.

That, and the pollution in Istanbul is getting to me. Artistic wealth, generous inhabitants, and baklava this city has in spades, but emissions controls not so much. My brother Robert is visiting and we spent much of Saturday walking through unexplored neighborhoods and hiking along the top of the 4th century Theodosian walls (the picture to the right is me talking to a dog in the slum next to the northern end of the city walls). Being able to wander aimlessly through centuries of history in a tank top in the middle of winter is a luxury I wouldn’t have even dreamed of in my four years of purgatory in freezing Cambridge. But, greedy as always, I would love to be able to spend the day outside and not feel like I smoked a pack of car-exhaust-flavored cigarettes at the end of it.